I woke up in a single-bed room on the 13th floor of Mirador Mansions, Kowloon. The room was a tiny box, with only a one-foot space between bed and door. Outside it was still dark. The window, barred like all in Hong Kong, gave onto a central shaft cluttered with corrugated plastic canopies, drainpipes and rubbish that blocked out all light.

Having flown in from New Zealand the night before, my body clock was four hours ahead of local time. I thought it was about 9am, but the darkness of the shaft outside suggested it was much earlier. So I lay in

bed, running over the images of my arrival still fresh in my mind: the eggy smell of the humid air as I stepped off the 747 at Kai Tak; then standing in the long queue for Immigration, watching the other lines go down more quickly than mine, and hearing two western businessmen behind me sighing and swearing:

'Come on, get a move on...'. Later, there was the disinfectant smell of an empty airport bus driving through the Kowloon streets at night: a Buddhist monk sat opposite me in a grey toga reading a Berlitz Hong Kong guidebook. And the Pakistani hotel tout who jumped out at me as soon as I got off the bus in Nathan Road, Tsim Sha Tsui, offering cheap rooms for $100 a night.

I don't know how long I had slept, but now I was unable 10 resist the call of my bladder any longer. I edged myself out of bed and squirmed into my clothes within the close confines of the four walls. The toilets were three floors up, via a grimy open stairwell. Outside it was suddenly daylight, and way below Nathan Road glistened in early morning drizzle, reflecting a few neon signs still lit up from the previous night. It was a chill, damp, spring morning and I was in Hong Kong, quite different from the placid autumnal Auckland I had left behind the day before. Already I could feel a hollow rumble of energy in the air.

For breakfast, like many foreigners travelling on the cheap in Hong Kong, I sought refuge in a place where I knew I could find a vacant seat, an English menu and a handy toilet: McDonalds.

Hong Kong was a city without seats, a place with nowhere to rest from the constant push of people, machines and noise. It was not a place to relax and smell the roses. Even at its most famous scenic spots like the Peak and the Star Ferry Terminal there was nowhere to sit and admire the view: lingering was not

encouraged. Likewise, there were no outdoor restaurants to while away an hour or two watching the world go by. Restaurants were for eating, meeting and doing deals, not relaxing.

Despite Hong Kong's affluence and budget surpluses, its public spaces were spartan, functional and unwelcoming - if not undergoing redevelopment. The parks were designed by somebody who hated nature: they had more concrete than grass, and the few park benches were rendered uncomfortable by iron dividers to prevent dossers.

Hence McDonalds was my refuge that first morning, squeezed into a yellow plastic corner reading my copy

of the South China Morning Post, with its amazing stories of hijacked ships, grenade attacks on jewellery

-shops and refugee camp riots. From here I couid plan my first day's mooching.

II

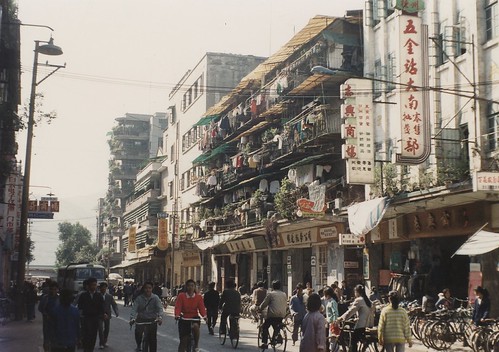

Hong Kong had been my home for a year in 1992. when I worked in the territory as a medical journalist. Now I was back, passing through on my way to China. On my first day I took a walk up Nathan Road to visit my old haunt of Yau Ma Tei, where I had once spent several weeks living in a cheap dormitory hostel.

Back then, I had been one of the lucky ones who had been able to move out into a flat. The other transients with casual jobs teaching English had no choice but to stay, living permanently in the dormitories with their private space demarked by towels and carrier bags.

This time round, my first impressions of Hong Kong did not agree with the previous jaded recollections I'd had of brash, cold and acquisitive people. The city seemed more subdued than before, not as arrogant or show-offy as I'd remembered. Perhaps it was just a hangover from the winter, but the locals definitely seemed paler and goofier than the bland, smug migrants who drove their Mercedes and BMWs round the posh suburbs of Auckland.

The office and shop workers marching 10 work looked Tired and more down-to-earth than their languid emigrant cousins in New Zealand. These were the ordinary Hong Kongers, the working people, not the flashy 'big-face' entrepreneurs with the hundreds and thousands of dollars needed to buy into another country and a better passport.

And to me, coming from the sunny colours and cheerful pastels of New Zealand, the people in Hong Kong seemed to dress in greys and blues. The only exceptions were the near little kids in bright uniforms skipping hand-in-hand with their Filipina amahs on their way to school.

The Kowloon streets had little touches of England, which together with the hustle and bustle, reminded me of London: the drab colours and dampness, the school uniforms and pasty faces, the double decker buses barrelling down Nathan Road, and the traffic lights that changed slowly from red-amber to green.

Yet amid all the Japanese department stores and plastic fast food chains there were still Chinese rough edges. Coolies in vests and rolled-up trousers pedalled stout black bicycles in among the traffic, ferrying toilet brushes and squawking chickens, while others trundled flat trolleys of wicker baskets full of rubbish.

Further north, lying on the seedier streets of Yau Ma Tei, were the worn-out bodies of homeless old men, with their greasy black necks and ankles protruding from under a piece of cardboard. They slept rough on camp beds in front of shops, under, cages of twittering birds, or amid the concrete 'recreation areas'. But Hong Kong's street-sleepers were not like London's 'Price of a cup of tea, guv?' beggars. They dossed but they weren't destitute: they still had work, but couldn't afford the sky-high rents, not even for the cheapest

caged-bed dormitory. There was no booze, glue or drugs, and the only beggars were the blind and hideously maimed.

Sleeping out in Hong Kong would be easier than on the cold, hostile streets of European cities. The humid heat of summer means there is little need for blankets and boxes and newspaper. Just the noise of the streets

to contend with: a crescendo of engines, pneumatic drills, the metal saws and the police sirens. And Hong Kongers were immune to noise: during my working days in Hong Kong I saw commuters dozing next to the open door of the engine room on the morning ferry, oblivious to the 100 decibel roar emanating from

within.

This was how I spent my first two days in Hong Kong: tramping the streets of Kowloon and Central, looking for nothing in particular. I went to visit my old office, where my former colleagues now regarded me as a hopeless eccentric, not to be taken seriously- They couldn't understand why anyone would want to visit

China for fun.

Two years previously, my workplace in Hong Kong had consisted of 30 Chinese, two westerners, three Filipinos and a Pakistani messenger. The westerners lived up to the acronym FILTH: ‘Failed In London, Try Hong Kong', and had a singular tack of interest in things Chinese. For example, my boss, who had lived in Hong Kong for seven years, would not eat rice and had never visited the mainland, forty minutes away by train.

'What would I want to go there for?' he had said. 'It's a dump. If I've got any free time I'll go to Thailand or the Philippines, not waste it going to that hole.'

Yet it was possible to pop over the Chinese border on a Sunday afternoon, explore the beaches and villages around Shenzhen, and be back in a Kowloon pub drinking John Smiths bitter and eating a Cornish Pasty by the same evening.

In our office there was an unspoken taboo among the 'gweilos' about socialising with the Chinese staff. In my first week at work, fresh from friendly New Zealand. I made the mistake of suggesting that our little section of secretaries and editors all go out for lunch together. This was met with dark looks and mutterings of 'He'll learn', from the old hands.

'They like to do their own thing, we do ours', they said later.

And so it was. The Chinese had been equally baffled by my suggestion, and proved impossible to get to know. During my year at the Hong Kong office I didn't make one acquaintance among the Chinese staff.

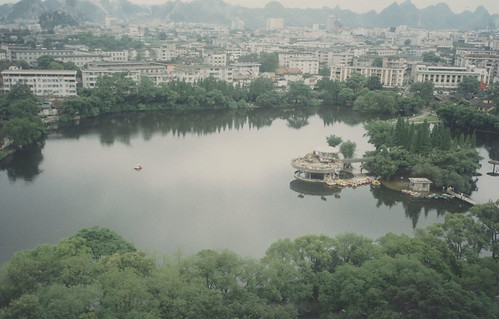

I might have put this down to language and cultural barriers, had I not been conducting a romance with a mainland Chinese girl across the border at the time. On my frequent visits to my girlfriend's home in Guilin, I would strike up conversations with all kinds of people, who were only too willing to tell me everything about themselves and invite me into their homes, or join their table for dinner. People on the mainland could be noisy and ignorant, but they could just as easily be frank, charming and endlessly hospitable.

Often I would return from such a weekend in China, full of enthusiasm from these encounters, only to hit a brick wall of indifference from the Hong Kong Chinese staff. I would try to start conversations about Chinese life, only to see them fizzle out within seconds – in the end I gave up and became another patronising gweilo.

The Hong Kong Chinese staff had a chip on their shoulder about the British. They regarded us as a separate species to be humoured, tolerated and obeyed. They put gweilos on a pedestal as the people who gave the orders and accepted all the responsibility. At the same time, they resented us foreigners and could not bring themselves to treat us as equals.

Attitudes towards work were also very different. When given a task, the Chinese staff would expect to he given exact instructions, which they would follow to the letter. They were industrious and uncomplaining,

but would never use their initiative, even to correct the most obvious mistakes. It was not uncommon for me, the rookie, to have to tell staff with 12 years experience how to do their job. "Don’t stick your neck out” seemed to be the unwritten rule.

The reunion with my old colleagues didn't last long. We said hello and swapped gossip, and I realised how small a place Hong Kong was for its 50,000 expatriates. They talked about their amahs and their little scams and their cricket teams, and between the lines of their conversation there was a sense of guarded isolation, as if a secret enemy was eavesdropping, everyone had their own little circle and I was out of the picture.

After two days on the streets of Hong Kong I tired of the incessant pace and the head-down, go-for-it rush. Everybody tore past me looking like they knew where they were going. The local Chinese would glance at me with bemused curiosity, as if thinking: 'Who is this nutter in the lumberjack shirt and big hiking boots?'

Some of their looks seemed almost pitying. It was time to visit Lantau Island.

An hour and ten minutes away by ferry, the barren hills of Lantau beckoned me away from the congested streets and exhaust fumes of Central. Lantau island is actually bigger than Hong Kong island, yet its population is a minuscule 50,000 villagers, fishermen, boat-builders and a few long-distance commuters. It

is a lush green island of beaches, mountains and holiday villas, with a few prisons, Vietnamese refugee camps and monasteries on account of its relative isolation.

Most people visit Lantau to see the huge bronze Buddha statue squatting on the top of the hills at the Po Lin monastery. Some go to visit the fishing-village-on-stilts at Tai 0, or to walk the empty hills on the Lantau Trail. I wanted to see how much Lantau had changed since I had lived there three years previously.

The Outlying Island ferries were a great mini-cruise experience in themselves. HK$6.50 to pass through the turnstile from a heaving waterfront throng of newspaper stalls and taxi stands, into a cramped caged pen to await the boarding of the ferry.

Once through the press of bodies over the gangplank, the choice was between the earthy lower deck, or for a few extra dollars, the air-conditioned refrigeration of 'De-luxe' class. My favourite spot was the sun deck at the stern of De-luxe. There I could sit watching the ripples in my condensed milk tea as the rumbling black and white ferry backed away from the jetty, out into the harbour traffic.

On the murky water there were craft of every description: small blue hovercraft wallowing in the swell, returning from Tuen Mun or Discovery Bay, red and white Jetfoils picking up speed on their way to Macau, large sleek hydrofoils waiting 10 pick up passengers for Shenzhen airport. There were dredging platforms and mainland tugs flying ragged red flags, their bridge railings draped with shirts and trousers hanging out to dry. There were flat barges with cranes loading containers, and there were sampan style pleasure craft (kai-do) and sluggish grey police patrol craft. There were the fishing boats; motorised junks without sails, flying the pennants of the sea gods.

And, as the ferry slipped away from Hong Kong island, the city's development came into perspective: the high rise buildings perched on a narrow strip of shoreline, above which rose the steep verdant hillside culminating in the Peak. A select few luxury developments peeped out from the higher slopes, and the peak was crowned by radio antennae. From a distance, Hong Kong island appeared neater and more modern than the noisy sprawl of street level had suggested.

Eventually Hong Kong island and Kowloon receded in a haze of smog, and the Lantau ferry wended its way through an armada of merchant ships at anchor. We passed a handful of small, overgrown islands, mostly rocks and bushes, though some concealed prisons or treatment centres for alcoholics. I spent the journey practising Chinese characters in an exercise book, to the hemu.sement uf a few Hong Kongers who stood watching behind me.

At Lantau I disembarked with a crowd of day-trippers and local residents pushing motorbikes and baskets of chickens. The tourists sprinted for the bus to Po Lin monastery, whereas I strolled over to a squat, yellow and red bus going to Tung Chung.

This bus, like all others in Hong Kong, had bars on its windows – I wondered what they were for. Someone had once told me the bars were to prevent damage in typhoons. But maybe they were just part of the Chinese obsession with security.

After depositing my fare (exact change only), I squeezed into one of the hard seats and held tight as the driver shot off up the hill. Lantau's bus drivers, I thought, held a key to understanding the Hong Kong psyche. Here on this sparsely populated island where the roads were relatively quiet, they still drove like

the clappers: foot hard on the floor, braking tightly around corners. I could understand this sort of behaviour amid the hurly-burley of Hong Kong island, but not here on this empty, bamboo-lined road where svelte Chinese cattle would occasionally meander over from the paddy fields. There was no tight schedule to keep: when the bus reached its destination it would sit idle for half an hour before returning. The rush was just the Hong Kong obsession with squeezing as much activity out of the minimum time. Time is money.

The bus skirted the southern coast road of Lantau, from where the sharp green-brown hills rose up gradually from the beaches of the South China Sea, up to the rocky barren tips of Sunset Peak and Lantau Peak. The thick bush of lower levels giving way to the scrub grass and occasional crags of the upper slopes.

The Tung Chung bus forked right and strained up a mountain road. over a cleft in the 2,000 feet hills, bringing into view the huge coastal airport development on the northern side. Where there had once been a sleepy fishing village -sheltered by a deserted islet called Chek Lap Kok, there was now a vast sprawl of

earthworks and reclamation, a huge swirl of cranes, trucks and portakabins. The small island had been flattened into a muddy brown smudge, and the once-peaceful shore of north Lantau now reverberated to the sound of engines, diggers, generators and the regular crump of rock blasting.

Surprisingly though, when the bus reached the centre of Tung Chung village, the small community appeared untouched by the multi-billion dollar development taking place next door. I sauntered over a walkway across the silty harbour, past fishing boats at anchor, and stepped into a maze of narrow alleys. Tung Chung was still the shonky. Jerry-built mess of concrete and hardboard I had first seen five years ago: poky little shops selling dried fish and shrivelled fruit, each shop protected by a little red box for a temple, with joss sticks and old oranges fur offerings. Old ladies in black smocks still peered suspiciously at me from their doorways, and I hurried through the narrow lanes, to emerge into the fresh breeze of abandoned paddy fields behind the village.

Beyond the coastal plain stood Lantau Peak, dark and gloomy against an overcast sky. Through the open fields I followed a ribbon path of concrete past a water buffalo, back towards the main road, noting the new developments: three-storey holiday villas with newly-tiled walls, and a large police station flying the Union Jack, looking so out of place. The police station looked enduring and slightly overgrown. But it hadn't been there a year before.

My plan was to walk up from Tung Chung up to Po Lin monstery and then climb up to Lantau Peak, where I would camp out for the night in the hope of catching a sunrise,

But first I stopped at the remains of Tung Chung fort, built by the Chinese in the last century to control pirates in the surrounding seas. Now all that was left were a few old ramparts and some restored cannon. The rest of the building had been converted into a primary school.

There were no other sightseers that weekday, other than a group of mainland Chinese officials, on a visit to see the progress of the airport. They were being taken in a Hong Kong police van and given a deferential commentary by their government minder.

We stood together and watched the school kids in their neat pale blue uniforms, line up and troop out of the fort like little soldiers. And I wondered how Lantau would change when the Union Jack was exchanged for the red flag.

VI

The path up to Po Lin passed several smaller monasteries hidden in the bushes. I had always wanted to visit these mysterious places after seeing their feeble, lonely lights high up on the hillside one night.

The first Buddhist monastery was the largest of the Po Un satellites. Its yellow prayer hall was emblazoned with a large Buddhist swastika, and gave out onto a forecourt with a sweeping vista of the Tung Chung plain. Nobody was about, so I sneaked round to a side door to look for a dining hall which I had heard

served vegetarian lunches. But everything was locked up and deserted: all I could hear was the slow Cantonese chatter of two nuns in the kitchen.

The path continued uphill through dense trees and bushes, passing several smaller temples. Some were locked and barred, others echoed to the sounds of daily household chores. Outside one of the larger temples, a Buddhist nun with a shaved head and a grey robe, looked up from tending a row of vegetables. She saw

me and looked away.

The bush around the track was alive with dragonflies and butterflies, while other insects hummed and squeaked in the undergrowth along with a few whooping bird noises. The track crossed a stream and I startled a pair of wild dogs scavenging from a rubbish bin.

I met no-one else on the track to the top, where the path levelled out below the crags of Lantau Peak and passed through an engraved yellow archway announcing the boundaries of Po Lin.

Po Lin had changed. It had always been a hit touristy with its small bus terminal and gaudy buildings. But now, thanks to 'Buddha fever', it had mushroomed into a mega-circus of sightseeing. The concourse beneath

the newly-opened giant statue of Buddha had been developed into a wide circular coach drop-off point that reminded me of the end of Mall at Buckingham Palace.

The roadside was lined with noodle stalls and trinket sellers and hawkers selling joss sticks. Chinese tour groups disgorged from coaches and snaked after their megaphone-toting, pennant waving guides. Each group wore identical baseball caps and name badges. They paused for solemn snapshots at the base of the statue before rushing to rejoin their group ascending the steps of the Buddha.

I turned my hack on this scene and walked hack into the trees, past a riding stables and a tea plantation, towards Lantau Peak. My guidebook described the path to the summit as steep and hazardous and said it was easy to fall off and kill yourself. But after my recent hiking escapades in the South Island, I found it a doddle.

Within an hour I was at the top, sat among grass and rocks in the doorway of a flea-infested public shelter, sheltering from the drizzle and cold wind. Everything was below me: the cluster of monastery buildings,

a smoggy outline of the hills poking through low cloud, a half-empty reservoir and the distant coastline.

Airliners would sporadically break out of the mist above to circle towards Kai Tak. There was no other noise apart from the patter of raindrops on the roof. At odd intervals a tannoy voice would echo up from Po Lin, hut otherwise I had the place to myself.

I felt rather lonely, watching the clouds close in below me, then dissipate to reveal a darkening landscape. There didn't seem to be much likelihood of a decent sunrise the next morning, but I wanted to stay and try out my new camping equipment.

The public shelter was squalid, nothing more than a six-foot high wall of rocks topped off with a roof of wooden planks. Inside, it was muddy and sprawling with rubbish in one corner. There were rat droppings on the bench. I wouldn't sleep in there.

As the light faded I chose a site just below the peak, a large flat rock ledge sheltered from the prevailing south-easterly breeze by a huge boulder. I pulled out my Thermarest air mat, stuffed my sleeping bag inside the bivvy bag, and climbed into my cocoon. It was 7.30pm and still raining.

The bivvy bag was nothing but a nylon body bag to keep the sleeping bag dry. In theory, k was made of breathable fabric that would prevent condensation. When I zipped myself in it felt dank and claustrophobic. There was just enough room to stretch out my arms and read a paperback by torchlight.

The wind and rain increased in force as the night wore on, and I couldn't sleep because the bivvy bag flapped and snapped in the wind - and I began to imagine I could hear rats chewing at my backpack.

Some time after midnight my worst fears were confirmed. I heard 'eek eek' noises and felt a small rodent body slither over my bivvy hag, scratching its claws against the nylon. I poked my head out of the bag and shone a torch into the mist. Under the rain-cover of my backpack, I could see a small body wriggling, just like the mouse under the carpet in a Tom and Jerry cartoon. 1 walloped it with my torch and it disappeared with a squeak. Wearily. I lifted up the cover to discover a three-inch hole chewed out of my backpack. The rats had been eating my muesli.

I didn't get much sleep after that. I dragged the backpack into the bag with me to protect it, which was a very light squeeze, and passed the rest of the night worrying whether rats were now nibbling through the bivvy bag. I glanced at my watch throughout the night: 2am... 3am... 4am, and the rainstorm increased in intensity. By 6am the wind had risen to such a strength I thought it would blow me off the ledge. I crawled out into a pre-dawn greyness and dragged the flapping bivvy bag, contents and all, through the teeth of the gale and into the relative peace of the shelter. Here I managed to snatch a couple of hours sleep on the bench, then awoke to a misty morning as the storm suddenly abated. There was no sunrise, but I consoled myself that despite the storm I had stayed warm and dry in my bag.

Bone tired, I packed up my wet gear and descended back down to Po Lin. The concourse was deserted and smothered with fog: silhouettes of temple buildings loomed out of the mist. I was the only customer at the noodle stalls when they opened at 9am, and the stallholders gave me suspicious looks: who was this dishevelled gweilo just descended from the mountain? I felt wasted. I needed a rest.

Before I first went to Hong Kong. the word 'expatriate' conjured up images of young ex-public school types in sleek suits living the colonial life in Their well-appointed Mid-Levels flats. These kind of people still exist in large numbers in Hong Kong but the other side of the coin is the Lamina expat. Lamina island is the haven of the down-at heel in Hong Kong, the home of drifters who came for a three-week visit and ended up staying three years.

Because of its low rents and relaxed lifestyle, Lamma attracts a diverse crowd of casual workers: teachers, waitresses, journalists and artists. In recent years the regular community has swelled with an influx of economic refugees from the recession-hit west. By 1994 the peak time ferries were bursting, and the narrow lane that served as a main street became one long conga of gweilos, making the local Chinese look like a minority on their own island.

After my wet, sleepless night on Lantau Peak, I went to spend a couple of days unwinding on Lamma. As if to bless my visit, the sun came out as I sat on the upper deck of the ferry on the way in. I looked around at the other passengers, contrasting the composed Chinese with the clapped-out, cynical expats. The gweilos looked so ungainly and sloppy beside the Chinese.

This contrast was typified on our arrival at Yung Shue Wan, the Mediterranean-like harbour on Lamma. As the crowds of Chinese commuters strode impassively along the jetty, they were suddenly thrust aside by a group of expats “GET OUT OF THE FUCKING WAY!' they screamed. A small group of pissed-up young expats pushed through, wheeling one of their mates on a home-made barrow. The Chinese continued on their wav, paying no attention, and I felt embarrassed.

On Lamma I stayed with a couple of friends whose flat was located on the first floor of a villa somewhere up a labyrinth of by-ways at the back of Yung Shue Wan. It felt good to be able to clean myself up, dry my clothes and then sneak out to hang out at the Waterfront Bar.

There were few Chinese faces in the bars of Lamma. It was mostly Brits, with a few Americans and Australians. Over their beers, the young expats grumbled about their lives in Hong Kong: how rude and unfriendly the local Chinese were, how the ferries were getting too overcrowded and flats more expensive, and the neighbours too noisy.

There were grumbles too, about work, although most expats were in Hong Kong simply because there were opportunities that didn't exist in London, Glasgow or Melbourne. In Hong Kong, the so-so could get a break into their chosen field of publishing, design, engineering or whatever, whereas at home they wouldn't even

have had their CV acknowledged.

Every so often a beeper would go off above the chatter of the bar, and somebody would sneak out to the phone, to find out about their next day’s schedule.

There were a few pseudo-westernised Chinese in the bars, but they looked out of place and over-the-top. In place of the neat yuppie wardrobe of the average Hong Kong Chinese, they wore exaggerated hippy or trampish clothes. And their behaviour was equally confused, picking up on the worst aspects of the western rebel image and bandying around 'fuck you’s'. It was as if by abandoning Chinese self-control for western freedom, they had lost everything.

The Sunday before I left for China, the weather was untypically clear and fresh. Recovering from hangovers, we went for a walk up the concrete paths of Lamma, out over the grassy hills to a vantage point overlooking the Lamma Channel and Aberdeen on Hong Kong island.

'Those are English clouds', my friend Paul said. looking up into the blue sky. 'I love clouds...', he said, and his scouse accent gave it a finality that made everything make sense.

I felt freshened up and ready to go to China.