I first came across Joseph Rock's articles about China and Tibet in the early months of 1991, soon after I arrived in New Zealand from the UK.

I was bored and spending a wet evening in the old Takapuna public library on the north shore of Auckland. In the upstairs reference section, overlooking the Hauraki Gulf, where boats bobbed in the windswept grey sea, it all felt very far away from the China I had just passed through and which had captured my imagination.

My interest in China had been piqued by my recent brief visit to the mountains of Yunnan, and I looked up "China' in the contents section of some very old back issues of the National Geographic magazine that I found on the shelves in a side room. I was curious to see what the armchair traveller of the 1920s would see in China.

Opening the pages introduced me to another world, the interwar years of America, where the advertisements were for Chrysler Imperial Eights, Palmolive Shaving Cream ("7 free shaves"), Furness Prince Lines ("12 days to Rio") and Hires Root Beer for Growing Children.

It also showed how we viewed the world differently back then. Articles telling me about "Syrians - the shrewdest traders in the Orient"...and "Seattle - A Remarkable City".

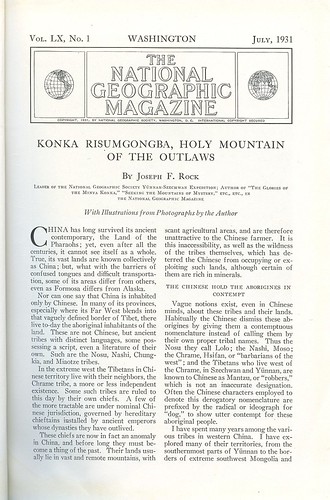

But it was the China articles that caught my attention. Or more precisely, it was the articles about remote areas of south west China and Tibet that intrigued me, with titles such as "Seeking the Mountains of Mystery - an expedition to the unexplored Amnyi Machen" in which the author, Joseph F. Rock declared himself to be 'the first white man' to approach this area, 'where no Chinese dares venture ...'. The photos were of spectacular mountain country, Tibetan warriors wearing leopard skins and posing with matchlock rifles, and primitive Yi tribesmen preparing to cross raging rivers with inflated pigs bladders.

In another article, "Konka Risumgompa - Holy Mountains of the Outlaws" the author declared that there were still areas of China that were most difficult of access and "whose inhabitants had defied western exploration".

I wanted to know more.

I looked at his hand-drawn maps and compared them with a modern Lonely Planet China guide that I pulled off an adjacent shelf, to see which areas he was writing about. But on the modern maps there was nothing there. Just a white blank space to the north east of Lijiang. The same with all the other Chinese guidebooks and atlases that I consulted. I was hooked - I wanted to find out more about these places in China that had been explored in the 1920s and had now apparently receded back into obscurity into oblivion.

But first let me explain how I got to New Zealand and why I shared with Joseph Rock an interest in south-west China.

In my late 20s, I was living a peripatetic existence as a medical journalist, drifting from one job to another, not really sure what I wanted to do or where I wanted to be in life. All I knew was that I craved travel, adventure and exploration like my literary heroes such as Patrick Leigh Fermor, Eric Shipton and Graham Greene.

I wanted to be or a modern-day Eric Newby, walking nonchalantly into the Hindu Kush and climbing a few peaks after a bit of farcical practice in Wales. The only problem was that I had no money. And besides, had I set foot in the Hindu Kush in the early 1990s I would likely find myself on the unfriendly end of an AK47 wielded by either the Russian special forces, a Mujahadeen or a member of the nascent Taliban.

China, on the other hand, seemed to be a good place to go for a bit of adventure. It was still Communist, it was still cheap and there were large areas of the country that were officially off limits to westerners, but which were slowly opening up.

When I first considered going there I was working in London as a reporter for a medical newspaper for GPs, based in Woolwich. For various reasons, I was thoroughly miserable and unsettled, both with London and my job.

I was not a professionally-trained journalist but had 'stumbled' into medical journalism after failing in just about everything else that I had turned my hand to since graduating with a degree in pharmacology from Liverpool University in 1984. I had tried the pharmaceutical industry and spent a surreal year as possibly the only 'alternative' medical representative to hit the doctors' waiting rooms of West Yorkshire on behalf of Astra Pharmaceuticals in a baggy suit resembling that worn by the Talking Heads' David Byrne in Stop Making Sense. Or in my case it should have been Stop Making Sales.

I had fared equally badly in the marketing department at head office. It seemed too much like Reginald Perrins' Sunshine Desserts for my liking. Like 'CJ' we had marketing managers who referred to each other by their initials.

My lucky break came when I was eventually given an introduction by my former university tutor to a fellow alumni who had become something in medical publishing in London. I thus gained my first toehold in the world of journalism, on the basis that I was one of a select few people who could not only spell medical words correctly but also understand enough to write a news story about them.

And so it was that I found myself working for 'the UK's leading magazine for doctors', based in a tower block in windswept Woolwich. It was a tenuous existence because I was not a member of staff. I was employed on a casual week-by-week basis depending on the whim of the editor. Every Friday I would be summoned into his office, where he would add up the number of hours I had worked that week and write me out a payslip in silence, always seeming to find some reason to deduct a few pounds worth of earnings.

He was a formal Jewish man who would then dismiss me with an awkward:

"Thank you. We won't be needing any help next week, but stay in touch ..." And I would, because I had nothing else.

The work, when I could get it, could be quite interesting. It might entail travelling to central London for a drug company press briefing at a swish venue such as the Naval and Military Club, followed by a nice lunch. Or attending a medical seminar held in a Regent's Park villa on the latest in contraception techniques conducted by erudite and witty professors of medicine.

Like most journalist jobs, though, it mostly involved sitting in the office and trying to chase people up on the phone to comment on the big stories of the day. And while I was reasonably confident about discussing medical matters with doctors, I still felt like an idiot because my northern accent was often misunderstood or greeted with condescension.

I couldn't even pronounce the name of my own paper correctly on the phone.

"You're from where ..? Pools ..?" the southern person on the other end of the phone would say. I had to start calling it Pals magazine, which after being processed by my northern vowels, came out something like how a southerner would expect to hear the word Pulse pronounced.

Being a recent arrival from up north, I didn't know anyone in London, and so even after a 'good' day at work I would return home on the tube to a lonely evening listening to Prefab Sprout in my bedsit in Clapham. I felt such a fraud in my Burberry raincoat and my flowery 90s tie, swaying along with all the other Londoners on the tube with their Booker Prize novels and their studied avoidance of eye contact.

I tried joining a few clubs, evening classes and playing in a football team, but like that other northerner Alan Bennett, I wasn't really a 'joiner'. I would occasionally go out to a comedy club or to see a band, but there is nothing so folorn or desperate as drinking by yourself in a London pub, surrounded by people who all seem to be having a great time.

Again, my accent didn't help. When I opened my mouth I sensed that everyone in London despised me as a yokel from the sticks. I missed the friendliness and directness of the north of England, but also its open and wild spaces. In the flat, grey concrete maze of Woolwich council estates I yearned for the moors and the dales. I read Wainwright's fellwalking guides and almost cried with homesickness at times. "The hills are my friends ..." he wrote. I felt that way too.

But there was no work for me near the hills. I had tried that many times before, on the last occasion forced to eke out a living working the night shifts at a phone bill processing centre for a wage that was barely enough to survive on.

And so it was that stuck in London I would seek solace in books, and daydream about going away on some challenging foreign adventure, to the hills.

I don't know where the notion of going to China came from, but it appealed for several reasons. Firstly, it was one of the last surviving major Communist states left in the world. After the fall of the Berlin Wall and the end of Soviet domination of eastern Europe, China seemed to retain a perverse desire to remain a die-hard Communist state. And it was literally die hard, as only a few months earlier we had seen the bloody suppression of the 'Tiananmen spring' in June 1989, and a seeming return to orthodox Communist totalitarian rule.

I had visited East Berlin and Prague in the late 1980s, before any inkling emerged that they may not last for another 50 years, and I had experienced that strange frisson of revulsion and fascination in being a voyeur from the 'free west' travelling in an Iron Curtain socialist state. I wanted to see what socialist China would be like, before it too became more capitalist. And I especially wanted to see what rural peasant China was like, rather than the grey industrial cities of Eastern China.

I also wanted to see China because I had read about it some exotic sounding places in a dog -eared guidebook entitled South-West China Off the Beaten Track that I found while passing a lonely rainy evening in Woolwich Public Library.

It described a China that sounded quite grim, very remote and in terms of entertainment utterly primitive. Not that different from Woolwich, really. The towns in Yunnan and Sichuan hat it described in pencil drawn maps generally had one hotel open to foreigners, one or two shops, a few noodle restaurants and if you were lucky, a bank where you might be able to exchange the Foreign Exchange Certificate 'funny money' that foreigners were meant to use instead of the people's money, renminbi.

Despite the recent 1989 crackdown, I sensed that this was a country emerging from 40 years of being a closed society. It appeared to me to still have the austere and monolithic framework of a socialist state, but the bonds were loosening and there were now opportunities to travel back into some of the previously out of bounds areas and to literally go off the beaten track.

Some of the descriptions in the guidebook gave tantalising glimpses of how the remote parts of the country had appeared to the first westerners to see them a hundred years ago. One passage in particular, described an impressive and previously unrecorded 18,000 foot peak on the upper reaches of the Yangste river near Leibo.

"As far as we know, nobody has ever DONE this region since ..." the authors wrote, after their own failed attempt to reach it, when they were turned back by police from the 'closed' area.

I was committed. I wanted to go to South West China. Little did I know that this would be the start of a lifelong interest.

No comments:

Post a Comment