What I had not realised in my confusion on arrival at Wachang was that the monastery and village were quite separate. Muli monastery was an hour's walk away, on the other side of a hill. But that did not matter right then.

An hour after my arrival in Wachang, I was the talk of the town. I sat with my feet in a bowl of hot water, in the village's only restaurant, devouring the dishes set before me by its beaming Chinese owner: fried pork, rice, egg and tomato soup. cold sliced ham, plus tea and heer. At the same time I chatted to the village's doctor and the local English teacher at the Middle school. They confirmed that I had arrived in Wachang, and that this used to he the old village of Muli. The 'new' Muli shown 100km away on my modern maps was actually the town of Bowa, which had become the administrative capital of Muli, hence its new label.

The English teacher, a bright young Chinese man, promised to take me to see the monastery the next day. He had never seen a foreigner before, and wanted me to visit his school to give a talk to one of his English classes. I told them about my journey in the footsteps of Joseph Rock, but they had not heard his name.

When I mentioned that I would like to visit other monasteries in the area, they shook their heads. 'All gone,' said the restaurant owner, Mr Zhang. 'There's nothing at Kulu now. It was all destroyed in 1958. There used to he 500 monks there, now there's nothing to see. Up the road at Waerdje there used to be 300 monks, now there's just a small prayer hall. And the big monastery here isn't what it used to be.'

The people gathered around me in the small shack couldn't believe I had walked over from Wujiao. They had never seen a foreigner before. 'Weren't you scared?' 'Did you meet any bad people?' 'What did you eat?' 'Aren't you lonely hy yourself?' 1 didn't care, I was in heaven. Food, drink, sitting down. I retreated to the luxury of a real bed, in the 'Post Office Guesthouse', where I could hear the people in the next room talking excitedly about 'the foreigner'.

Even the bedbugs couldn't stop me from getting to sleep. I didn't know quite what I expected to find when I visited the Muli monastery. Certainly it would not be the centre of the old 'lama kingdom' any more. The Tibetan monasteries hereabouts had been destroyed in the late 1950s, well before the Cultural Revolution, because they were the centres of political as well as religious power.

Even Rock had the foresight to realise that the days of independence would soon be over. 'These chiefs are now an anomaly in China, and before long they must become a thing of the past', he had said of kings such as those at Muli. In fact, life under the Muli potentate was servile and archaic. Rock noted that the Muli villagers walked around with bowed heads because they were forbidden to so much as look a monk in the eye. The king, although described by Rock as amiable, ruled despotically, served by a court of Yellow-hat Buddhist monks. He kept the mummified remains of his uncle in a gilded shrine in the dining room, and had his turds moulded into pills which were given to the peasants to cure disease.

The king had not known whether China was ruled by an emperor or president, and believed he could ride on horseback from Muli to Washington. The Muli kingdom had been poor, its 22,000 inhabitants served hy a few terraces of wheat on the hillsides. The peasants survived hy cutting grass, which they sold to passing caravans for horsefeed. There was some panning for gold in the Litang River, the proceeds of which went to the monastery. The land was often not enough to feed the local people, who as a result became enslaved to the local monastery if they could not pay for their food.

A local folk song went:

'Eight or nine years work earns only 13 bags of rice,

Sell all your property hut still not enough to buy food.

Give your wife and daughter away,

And be whipped and thrown into, jail.'

In this respect at least, Muli had improved somewhat. I had steamed bread and cabbage for breakfast the next morning, and met the English master for a visit to the monastery. We climbed a path above the town, to a burnt-out barracks and the remains of trenches used by the PLA to defend Wachang from marauding bandits in 1958. The area had been plagued by bands ofTibetan robbers who periodically emerged from their mountain hideouts to raid as far as Lijiang.

'What happened to them when the PLA came?' I asked. 'Defeated of course!' said the teacher, smiling.

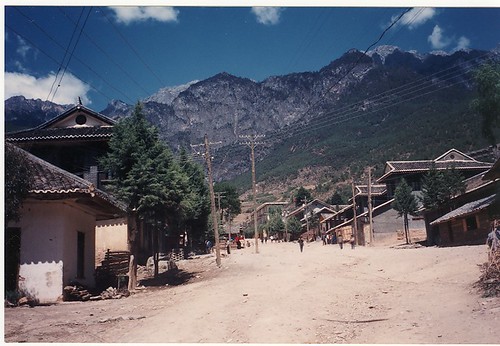

Over the ridge and through an archway, we had glorious views in both directions. To the west was the valley I had descended the previous day, and the neat rectangular walled village of Wachang just below. To the east, green terraces descending into the vast Litang River valley beneath. Up here. the soil was brown and barren. Beyond, the mountains rose up, black, their details cast into shadow. And overlooking everything else were the mighty blue-grey towers of Mt Mitzuga, standing out against a deep blue sky. We walked around the hillside and I asked questions about the monastery.

The teacher told me there were now 50 young lamas under training at the Muli monastery, young apprentices recruited from among the local Tibetan population. Most of them could not speak Chinese, hut he would translate, he said. For the time being, he was more interested in finding out which countries I had visited, and how much I earned. The first building we came upon was a white hut straddling a stream. Within was a large yellow prayer wheel, turned by water power, sending its blessings spiralling into the bine sky. Twenty minutes later up the dusty track, we rounded the corner to Muli monastery.

When Rock arrived at Muli, it was a 400-year-old lamasery of 300 houses and temples, surrounded by a large white wall. It was one of three large monasteries that served the Muii kingdom, and was the home of the Muli king. Rock entered Muli with his retinue of Siamese, Tibetan and Nakhi servants, bearing the gift of a rifle for the king. He was greeted by the 'prime minister' and other king's servants, clad in red robes, who escorted him to the palace square to the sound of 'trumpets, conch shells, drums and gongs, besides weird bass grumblings of officiating monks.'

My own arrival was a little more low key: greeted at the gateway by the head lama and a group of teenage monks, all clad in maroon togas and wearing PLA plimsolls. The grey-haired lama wore a silver-pink waistcoat under his gown. Only a few buildings remained of the once-great monastery. As expected, most of the buildings had been systematically taken apart, the building materials used elsewhere. A few tooth-like skeletons remained of the larger halls and palace.

The one building that did remain, or had been rebuilt, was a large white temple with an orange roof. Further up the hill, beyond a sad scattering of ruins, was a second temple being rebuilt on the site of the most sacred of the former buildings. It was a beautiful pace despite the fallen glory. Bathed in the spring sunshine, the white buildings had an unearthly air as they dominated the valley and mountains beyond. Full of excitement, I was led through to the courtyard, where young monks squatted over easels, bowing their heads and reciting the sacred scriptures. Their chanting suddenly died down as they realised a foreigner was present. This was the culmination of my trip. and I felt slightly in awe of the place.

The lama invited me in to take pictures and left me alone to wander about- Within the main prayer hall was a modest 10-foot high gilded Buddha. This was no match for the 50-foot high golden statue that Rock had seen in the same place. 1 wonder what had happened to it. In the back of the room was a row of warlike gods, representing the spirits of Mt Mitzuga: they rode ferocious green and white lions and were armed with hows and arrows, or swords. Some of the gods had several pairs of arms and legs, others had crowns of skulls. All of the statues were robed, in deep hues of blue, orange, green and pink. Leaving the English master behind, I climbed up the hill beyond the monastery to photograph the temple from the spot where Rock had taken a picture entitled: 'The Lama City of Muli on the slopes of Mt Mitzuga'.

The contrast was startling. Now the walls had gone, and the once tight cluster of white buildings was reduced to a few slumps in the arid brown earth. A pair of swifts rushed over my head, wheeling around for insects. The atmosphere of this new Muli made me want to leave: the ghosts of the old were still around, and they pushed me away. Before I left, I asked the lama about Joseph Rock, but he said he had never heard of him. The lama spoke little Chinese, and seemed reluctant to talk via the English master, he just smiled, and waved around the place, urging me to see for myself.

No comments:

Post a Comment