The local Yi people were yelling at their plough oxen, trying to stir them into action, and cuckoos sang hidden in the pine forests ahead. When I left the plain and ascended into the pine forests, I began to feel nervous, as if somebody were watching me. I fingered the Tihettin knife, which I now kept handy in my pocket, and I Jumped at every broken twig. Then, when I stopped for a drink, I heard a 'plop' beside me. and looked up to see an old man and young boy sat a few yards away, laughing at me, and about to throw another stone. They told me they were on their way from Wujiao to Youngning, to sell their home-made firewater at the market.

I asked the old man about the villages on Rock's map. Yes, he said as I tried to pronounce them, they were all still there- It was somewhere around here that Rock's mule caravan had come across a cavalcade ofTibetan monks, dressed in red robes and escorting the brother of the Muli king. The monks hurled abuse at Rock's party, telling them to get out of the way. Rock retaliated with a stern lecture and even more dire threats, which prompted the lama to capitulate with the Tibetan gestures of deference: sticking his tongue out and giving a thumbs-up gesture. The royal party passed without further communication. Sadly, the virgin alpine meadows that Rock described in this area were no more. 'No woodman's axe has ever echoed here,' he said of the metre-wide fir tree.s he saw. But the pine forest I saw in 1994 had been logged haphazardly, with whole swathes taken out of some hillsides and others left intact. It was the handiwork of amateurs, smaller trees discarded and left to rot.

The few meadows I came across were scarred with campfires, and rutted with well-worn tracks. And on either side, landslides had swept down the eroded hillsides, churning up trees and earth into ugly, twisted heaps. Yet there was still some beauty left. When I crested the ridge, the mountains of Muli came into view, larger now, and an impressive sight against the clear blue skies. Forested hills extended as far as the eye could see, and I could have been in the South Island of New Zealand. Below me, in the valley, was Lijaisuin. the first village in Muli territory. It looked like it hadn't changed much in the last 60 years: primitive log cabins, with the only power source being water wheels.

The village itself was deserted, with everyone working in the fields. I asked directions from an old woman tending goats, but she just splashed her feet in a stream and giggled in a high-pitched voice. I had the same problem higher up in the forest, when I asked two young goatherds the way to Wujiao. They spoke no Chinese at all, and gestured mutely towards the top of the hill. Not surprisingly, I was soon lost in the sparse forest, but eventually 1 fought my way up along goat tracks onto the next ridge, for an even more impressive view of the mountains.

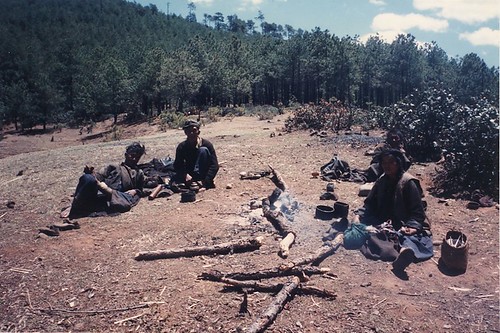

Suddenly, I heard voices, and came upon a group of wretched Tihetan nomads, wrapped in animal skins, sat around some smouldering logs. They had blackened faces and were eating what looked like raw meat off the bone. They eyed me suspiciously when I asked the way to Wujiao, and I left with their dog snapping at my heels, heading down into the valley.

By late afternoon I was parched. Tramping down through the pines and blooming violet rhododendrons, I craved water and wondered how much further it would he to Wujiao. Not much further, surely. My heart sank when I saw the collection of fly-blown log cabins with no sign of a guesthouse or shop. When I got there, I was so thirsty that I begged a bowl of dirty water from a Yi woman who emerged from one of the kennel-like huts, and drank it straight down without fear of disease. In her dirty black Darth-Vader-like robes, she stared at me and pointed further down the hill. 'Wujiao...' she squeaked. Thank God. this wasn't it.

The real Wujiao was a barrack-like group of buildings, with a single shop in a courtyard. Two Tibetan girls sat by the roadside drinking spirits, and they invited me over to rest and share their firewater. But I wanted water desperately. 1 stumbled onto the wider path that was the main street, and in front of a kiosk met a small Tibetan man in blue Chinese working clothes. There was no running water here, he said, but he invited me into his shed and built a fire to boil me some hot water. I sat, exhausted, but glad to have finally found someone who could speak passable Chinese.

No sooner had I sipped my first bowl of sooty-flavoured water than I heard a car engine. Strange, I thought, because there were no roads around here. I rushed out to see a Jeep screech to a halt, from which emerged three men brandishing automatic weapons. I froze with fear at the sight of the guns, and prepared to he frog-marched off for interrogation about why I was in a forbidden area. The men were in civilian clothes, and their leader was a suavely dressed Chinese just like the plain-clothes cops I had seen in Guilin.

He walked up to me and held out his hand to give me a firm handshake, with a friendly 'Ni hao! Ni hao!' Where had I come from? I told him about my walk over from Youngning. 'Wow! That's tough! I really admire your spirit,' he said, and explained that his Jeep group were Party officials from Muli county who had just driven over a rough mountain track to inspect this village. It took four hours by car, twelve hours on foot. he said. Meanwhile, the Tibetan shopkeeper came running out with a live chicken, which he pressed on the leader. The leader made a show of trying to refuse, but the shopkeeper insisted: 'It's nothing, realty..' he grovelled.

I still felt nervous with the guns being toted around, especially as the two other goons looked at me coldly. But the young leader, exuding menace and power in his leather bomber jacket and neat stacks, simply patted me on the back and wished me good luck for my trip to Muli. 'Sorry we can't give you a lift. Full up!' he said.

With that. the Jeep took off again, leaving me and the shopkeeper both looking relieved. I went back inside to finish my water, and asked about the old lamasery ofRendjom Gompa, which the shopkeeper told me was only a half-hour walk away. The track down to the monastery followed a river through a stunningly beautiful gorge with dangerous-looking overhangs. Out the other side, perched on top of a grassy hill was a small white building with a backdrop of mountains and pine forests. This was the one-man lamasery of Rendjom Gompa.

The lama, Aja Dapa, beckoned me into his dim scullery, where a young boy helper prepared butter tea around the fire. Neither spoke much Chinese, but they treated me with simple hospitality- The lama was a burly Tibetan in a maroon robe, who laughed heartily when I passed on the message from the Youngning policeman.

I drank my muddy tea and tried to comprehend the lama's fractured Chinese. He said his lamasery was not worth seeing: the place was falling down, the roof leaked and there wasn't much to see. The lama had been in residence there for four years by himself, sent from (he main monastery at Muli, now known by the Chinese name of Wachang. Unlocking his temple, he showed me the faded, soot-blackened murals on the humpy walls. In the dim light it was just possible to make out the reds and yellows of horses and gods against a black background. And white scars where the faces of deities had been chiselled off during the cultural revolution.

'You'd be better off going to the Muli Main Monastery, much more beautiful than here,' he said. Wujiao was a rough old place. Young Tibetans wearing crimson chubas, stetsons and long knives, herded around a couple of pool tables, playing clumsy potshots that sent balls flying off the table. And they stared at me wildly when I walked among them. It didn't feel safe.

There was nowhere to stay in Wujiao, but the shopkeeper took pity on me. He arranged a few bits of sacking on the floor of his cabin for a bed, and prepared me a disgusting evening meal of noodles with fatty gruel. Two tall Tibetan girls in modern dress came and stood in the doorway as I choked the food down, They shouted questions at me in yelping voices, and couldn't take their eyes off me. 'You look handsome,' said one. 'But you've got a big nose!' giggled the other. 'You're quite an interesting person,' said the first. Hello, where's this leading? I wondered. But then they disappeared.

I saw them later in Wujiao's only room with electricity; the video hall. The whole village, some seventy people, turned out to watch some Hong Kong videos dubbed into Mandarin. I wondered what these country folk made of the Kowloon high-rise estates and the British road signs they saw on the screen. When I returned to the shopkeeper's cabin, he brought some of his mates round to look at me. They sat on the floor, drinking firewater and pinching the hair on my arms. 'You must have a lot of hair on your chest, and down there too, eh?' one said, gesturing at my groin. I turned over on my bedding, pulled a spare chuba around me and tried to give the hint that I wanted to steep. Eventually they tired of talking about my strange boots and my funny eyes, and left. I tried to ignore the moonlight and cold wind seeping in through the gaps in the logs.

Tomorrow would be a long day, and it was time to hit the sack, literally.

No comments:

Post a Comment