On his first visit to Muli, Joseph Rock spent three days being entertained by the king, taking portraits and exchanging gifts. Rock became good friends with the Muli king, and was to return on several occasions to Muli, to use the monastery as his base for explorations further afield. The king was a jolly fellow, 36 years old. with a round figure and weak muscles because he never worked or exercised. The lama king had once been a living Buddha, and in 1924 he was surrounded by cringeing lama courtiers.

They crawled in on their hands and knees and would not dare look at the king until he had touched them on the shoulder. When they left his presence, they would shuffle backwards, not daring to show their backs to the king. Rock was invited to dine with the king, and after a lecture on western life, he joined the king to partake in Muli delicacies: butter tea and yak cheese interspersed with hair, and cakes as heavy as rocks. The explorer's party was also presented with gifts of eggs, rice, wormy ham and lumps of salt. In exchange. Rock gave out silver coins and three cakes of scented soap ('the greasy black necks of all the lamas, including the king and Living Buddha, showed that soap was not in demand.')

Rock's caravan had brought a great deal of photographic equipment, and he took it on himself to take special portraits of the Muli king and his court. The king sat on his throne, surrounded by the best furniture and carpets in the palace, and posed in his most ceremonial rubes. Rock also recorded the king's deputies: his military chief, the chief magistrate, and the Living Buddha on horseback. As a reward, the king sent a procession of 40 lamas the next evening to Rock's living quarters, to scare away any devils. They did this by blowing on their long trumpets and building a fire, onto which they threw effigies of lurking devils. Altogether, Rock stayed three days at the palace of Muli before returning to Lijiang.

On his departure, the king presented him with more gifts: golden bowls and leopard skins. He was seen off by the king's secretary, and given an escort of eight men, who went ahead each day to prepare a campsite while they were still in Muli territory. Rock was impressed by the courtesy and hospitality shown to him in Muli, and was sad to leave. 'A peculiar loneliness stole into my heart,' he wrote when he left, 'I thought of the kindly, primitive friends whom I had just left, living secluded from the world, buried among the mountains, untouched by and ignorant of western life.'

I felt little regret when I left the monastery after my brief visit. I returned to Wachang, around the hill, a much jollier place by far. The English master had deserted me, and I walked hack alone. The Muli monastery was now a pitiful place compared to its former glory, but on the other hand, the local village now echoed to the raucous cries of the classroom. At one end of the humpy main street (there were no cars or roads to Wachang, the nearest highway was down in the valley) was a primary school, where children could be heard rehearsing Tihetan peasant songs. At the top end of the street, the Middle school kids just yelled out of the windows at me.

Wachang, whose name literally meant 'tile factory', had become atypical Chinese small town. complete with high rise blocks topped with satellite dishes. It has a Post Office, a Tibetan guesthouse and a store that sold the basics of rural life: daggers, pictures of fluffy kittens and more beer juice. As I walked up the main street I saw a young girl sat on a .stool ouiside a kiosk, with an intravenous drip of glucose in her arm. This was a popular Chinese 'remedy' for listlessness.

Further up the street I was called over by a rough-looking man squatting against a wall. I was a bit fed up with being pestered by everyone in town. hut something in his manner made me go over. 'ID card!' he snapped, as 1 arrived, and he whipped out his police card. 'Where have you come from?' he barked as he flicked through my passport. When I said Youngning, he asked to see my closed-area permit. I played the fool and showed him my Chinese visa. He seemed content with this and let me go. A close call, I thought.

In the afternoon I went to give a talk to the English class at the Middle school. I was expecting a class of about thirty kids, so I got a shock when I walked into the playground to see the whole school of 200 pupils assembled, staring at me in excited anticipation. The teacher had rigged up his karaoke machine as a makeshift PA, and my hesitant Mandarin emerged from the speakers in muffled, triple echo. 'Teach them a few words of everyday English,' the teacher said, so I told the pupils to say 'Hi' instead of yelling 'Allo!'. I toyed with the idea of getting them all to say 'Have a nice day', hut I settled on the more mundane 'How are you?' instead. And that just about exhausted the snotty-nosed crowd's memorising ability.

'Tell them how important it is to learn English,' said the teacher, 'Many of the pupils are not enthusiastic.' I tried to explain that English was the international language, and useful in many different fields. But what use was that to a village full ofTibeian kids who would probably never meet a foreigner, and who would end up working in the fields? Just when I was getting into my stride, telling the kids about our strange English habits ('Never ask an English person how much they earn, or how many children they have...'), the teacher told me to wind up with a song. The only one we all knew was Happy Birthday. The gathering broke up, and for the rest of my stay in Wachang 1 was plagued by shouts of 'Hi! How are you?' from the school windows.

Meanwhile, I went for a peep at the spartan classrooms, and gave a reading of 'The Farmer's Buried Treasure' in English to one of the classes. The school was the social centre tor the kids of Wachang. They were at the windows, shouting, from first thing in the morning until I retired to my room at night. The classes finished officially at 8pm, but the pupils hung around, doing their homework, or practising their disco dancing steps in formation, to seventies western music played on an old cassette.

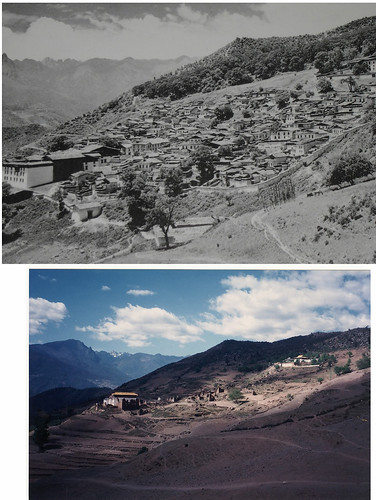

Modern Muli was a world away from the kingdom of cringing peasants of sixty years ago, when the villagers lived in fear of the monks. It was still poor, but not wretched: everyone had enough to eat. There were secret policemen, but the one I saw on the street later invited me over for a game of cards. I realised that the Muli kingdom I had come looking for was no longer there: Muli was now just another small corner of the Great Chinese Socialist Family, with all the fruits of 'Socialism With Chinese Characteristics'. The quaint, despotic monks had been replaced by the all-pervading influence of the Party, and its now pragmatic slogans of socialist construction. The colour and culture of Muli had been eradicated in the name of Mao, and now it was forgotten by the young generation, whose desires and pastimes were similar to those of millions of other Chinese.

Back in the shack restaurant that night, I met a 'Minorities Expert' from Chengdu. I could tell he wasn't from Muli because he was wearing a tie. He had been sent from the Minorities Institute to document the fast disappearing traditions of the more remote mountain tribes in Sichuan. At last, the Chinese were doing something to preserve the cultures that they had so long tried to suppress. But this man had little time for Muli and its people, whom he dismissed as just diny Tibetans. 'That's why I only eat at this restaurant, because it is run by a Chinese and therefore the hygiene is OK. The Tibetans don't even wash their hands,' he told me confidentially.

The man was Just using Muli as a stopover on the way to visit some other matriarchal Mosuo people, further to the north. He warned me not to venture into the hills around Muli because of bears and Tibetan robbers. 'Was that why the men I saw in the jeep were carrying guns?' I asked him. 'No, that would just be for shooting birds,' he replied. But it didn't seem likely to me. You don't use an AK47 to bag pheasants. 'Destination Konkaling' had been the unofficial theme of my trip. Konkaling. the mountain lair of the bandits in Rock's day. Now the Chinese called it Gong Ling and had put a road in there. It was only forty miles to the north, but the road went in from the northern side, and would mean a 10-day trip going back via Lijiang to get there.

I went for one last look. up to the ridge above Muli. to survey the countryside. And I realised that walking to Konkaling from here was not on. The sheer scale of the mountains, plus my lack of supplies and equipment ruled that out. I had been lucky so far, getting to Muli with nothing more than a knapsack full of peanuts and biscuits. But that sort of approach would not get me to Konkaling: it would need camping equipment, proper food and a portable stove, and prefenshty a few companions, for safety.

As I looked over the to the rise and fail of the huge hills, I realised this was the end of my trip. From here on, it would be homeward bound all the way, and I would have to set my sights on some new target. I would leave Konkaling for someone else to discover again: it was probably Just another Chinese outpost by now, something like Wujiao or Wachang, with log cabins, pool tables, karaoke parlours and logging trucks. But it still nagged me that I would never really know.

No comments:

Post a Comment