I threw out my sleeping hag, books, maps and other junk, and restricted myself to a raincoat, thermal underwear and toothbrush. Then I went shopping for food. There wasn't much available tor the potential trekker. I had to make do with peanuts, chocolate, green raisins, beef jerky, powdery biscuits and a packet of dried prunes. Fresh fruit and drinks I could buy along the way.

The night before I left Lijiang for Lugu Lake there was something going off in the town square. Young women of different minorities milled around in groups, flirting with the young 'liumang'. The Nakhi girls wore blue capes with seven white circles on their backs, representing the stars -10 show they held up the sky. Bai women wore a collage of pink. while and blue and the Yi women had several layers of pleated dresses in reggae colours: red, green, yellow and black. They also wore the craziest hats: a flat black square like a graduate's mortar board, with one corner facing forward.

The men were much more drab in appearance: they wore the standard Chinese suit jacket, complete with label still stitched to the sleeve. Likewise, they wore cheap square sunglasses with the sticker still on the corner of the lens. There was something in the mainland Chinese psyche that made them leave the labels and wrappings on their purchases: new cars would still have the barcodes left on their windscreen from their Japanese shippers, bicycles would be pedalled round with the plastic padding still wrapped around the frame. Even sofas would retain their cellophane wrapping for weeks after their purchase. In China it was important to show the brand ('paizi') and to show off something new.

A two-day bus trip over heavily-eroded hills took me deep into Yi territory before Lugu Lake. These were the (Lesser) Cool Mountains and the Yi were a wild, poor people who tilled a barren yellow soil. 'They are very backward. They do not wash,' the Chinese in Lijiang said about them. Even the Nakhi compared themselves favourably with the Yi. 'We Nakhi are the best educated of China's minorities. Unlike some other minorities (ie the Yi) we have a strong culture,' they said.

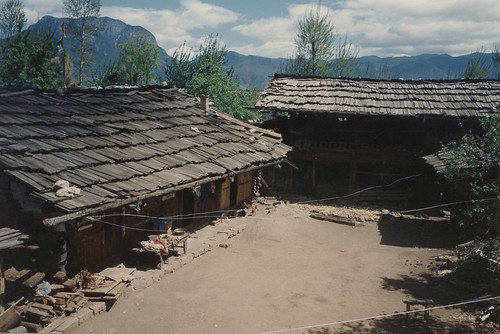

In the countryside around towns such like Ninglang, the Yi were dirt poor, literally. Their dwellings had changed little since Rock wrote: 'The houses of these primitive people are of rough pine hoards, tied together with cane, and the roofs weighted down with rocks,' I saw a few Yi women close up after they squeezed on the bus. They had freckled weather-beaten faces and wore grubby, unwashed traditional dress. They had round eyes, aquiline noses and high-pitched, coo-ing voices- I could well believe that until forty years ago, they had been a slave society, despised by the Chinese and given the derogatory name 'Lolo', ('wog'). The Yi had until recently been divided into noble 'black' Yi and their 'white' slaves.

The Yi in this particular area were originally outcasts from the main Yi area north of Lijiang. and thus were doubly wretched. Liberation had brought them freedom, but little else in the way of development. They were the some of poorest people I saw in China.

Lugu Lake, in comparison, was an earthly paradise of abundance. The blue waters twinkled in the sunlight below the crags of Lion Mountain. Cuckoos sang in the forest and the air was fresh and cool. The local people, the Mosuo, were famous for being a matriarchal society of 'free love'. They were an obscure branch of the Nakhi minority, a cheerful and robust people who built strudy wooden manor houses around the lakeside and fished the lake in dugout canoes.

But when I arrived, I was not in a mood to appreciate all this. I had been violently sick on the bus coming in, after eating a dodgy pancake bought in one of the Yi villages en route. The final day's journey had been a nightmare, bouncing along on the back seat, trying not to throw up. On arrival at Lugu Lake, I was too weak to stand up. t vomited in the courtyard of the guesthouse where we were dropped off, and collapsed into the first room they could find me.

For the rest of the day I shivered under the blankets with all my clothes on, and cursed myself for leaving my antibiotics hack in Lijiang. By evening I had recovered somewhat, and, as luck would have it, I bumped into some American friends who gave me antibiotics and moral support. They were staying in the next village, and I was guided to them by a cheerful group of engineers from Chengdu who had seen my plight on the bus. After searching through a maze of paths and passageways in the blackness, we tracked down the Americans to a dark, spacious living room off the courtyard of a Mosuo house.

Sat around a crackling fire. Will and Eileen (from LA) told me about their 'find'. They had become so enchanted with the tranquillity and beauty of Lugu Lake that they had extended their stay to a week. They were particularly delighted at being able to stay in a Mosuo house amidst all the pigs, cows and geese. Being a Mosuo household, only women lived in the house: mother and aunt in traditional blue-black gowns and turbans, the daughter in modern Chinese dress.

The father, referred to as 'uncle', lived elsewhere, but popped in regularly to see how things were going. Mosuo women would have several different lovers before they married. A couple would be regarded as ‘wed' once they had produced a baby. The woman would then bring up the child in her own mother's house, without a live-in husband.

Will and Eileen told me they had been staying with this Mosuo family for a week, living off a horde of vegetables they had brought in from Lijiang. Apart from potatoes, there were no vegetables to be had at Lugu Lake, they said. The Mosuo women cooked up some barley sugar crisps that helped restore my energy. Then I wandered back round the lake in the moonlight, past a few fisherman huddled round fires.

I was now within the realms of Joseph Rock's hand-drawn maps. He had spent two months at Lugu Lake, seeking refuge on one of the islands from a hunch of disgruntled Tibetan rebels who had been repulsed from an attack on Kunming. The island still had the small lamasery shown in Rock's pictures, attended by a chanting monk. Nowadays the local villagers rowed tourists out to the island in dugout canoes. Walking back round the lake the next morning, the water lapping quietly on the shore, I saw one of the canoes being paddled out to the island. The sight of the oars rising and falling, and the sound of shouts and songs carrying over the water, all reminded me of the New Zealand Maori war canoes, the 'waka'.

Further along the shore. I came across a friendly group of art students from Chengdu. squatting with their pallets and doing watercolours of a white sione stupa by the lakeside. Nearby, the villagers were building a two-storey hall completely out of wood, using no nails. I moved into the Mosuo family house and spent a lazy day recuperating from my stomach bug. Within the courtyard, sheltered from the gusty winds, I sat reading my maps among the piglets, geese and calves. According to Rock's 1924 map, Muli monastery was a 50-mile walk to the north-east of Lugu Lake.

After the nearby town of Youngning there were ru; other features to follow except for a couple of villages. I would just have to ask my way as I went along. Back in 1924, Rock had done the journey from Lijiang to Muli by mule in 11 days. He described it as: 'One of the most trying in Southwestern China... it takes a hardened constitution and great powers of endurance to make the trip,'

With my wobbly stomach and dwindling supply of peanuts, I didn't feet quite up to it. Decent food was not easy to come by in these country areas. The Mosuo seemed to survive on a simple diet of potatoes, fish, eggs and chillies. There were few other vegetables to be had. Luckily, Will and Eileen stilt had some stocks left. Each mealtime they would give the Mosuo mother a cucumber or some tomatoes to fry up. An hour later we would be sat in the dark living room with a few beams of light coming through the roof, eating a dinner of potatoes, sausage, eggplam. egg and tomato soup, corn wine and tea. The old lady would sit in a corner making butter tea with a plunger device.

Despite its beauty, Lugu Lake was a low point tor me. ! was growing sick of China, fed up with bus travel and poor food, the stares and the sniggers. But more than that, I had found I wasn't cut out to be an explorer: I missed my home comforts. After a month on the road, all I wanted was to be sat in a cafe sipping espresso and reading a decent English newspaper.

Before coming to China I had fancied myself as a bit of an adventurer. Yet here I was, thinking the journey to Lugu Lake had been an arduous venture into the unknown, while these Californians were treating it like a visit to Disneyland. They didn't speak a word of Chinese but were right at home, communicating with enthusiasm using a few grunts, grins and sign language. Meanwhile, I felt like I was at the edge of the world, and my attempts at speaking Mandarin were met with puzzled frowns from the Mosuo. I'd had enough of China and I wanted to go home. When the Americans said they had found a lift alt the way back to Lijiang for the next morning, I wanted to go with them. Somehow I managed to resist.

It was with some reluctance that the next day, after a breakfast of roast potatoes, steamed bread and butter tea, I said goodbye to Will and Eileen. They were going back to Lijiang, I would carry on. There was no bus to Youngning, 20km north, so I started walking. In the middle of the village I passed one of the art students, carrying her paintbox disconsolately up the road, looking for inspiration. I felt the same way. But as I left the village behind and climbed the road above the lake, I felt happier, freer to be among the wind, the sun and the bird song. It was good to be doing something rather than just sitting around. I started to sing to myself, and plodded the next four hours, over the pine-clad hills and onto the Youngning plain.

No comments:

Post a Comment